My small hands worked diligently with the Little Tikes Waffle Block set on the floor. They were building a house spacious enough for my large family, with a room for each of my ten siblings and one for my mother, a petite Hispanic woman from Honduras. I wanted my favorite colors, pink and purple, to outline the exterior of the house.

In my heart, I believed that we would be a family free from the clutches of poverty, abuse, and mental illness. Those problems couldn’t coexist with me in the house I was building. I couldn’t wait to see my family again and asked my foster parents if it was time to go.

They gently brushed my blondish hair and told me we wouldn’t be leaving until the morning. “Sarah, we have to wait for Ms. Gloria to meet us at the house.” Ms. Gloria was my social worker from the Department of Children and Family Services in Louisiana where my family resided.

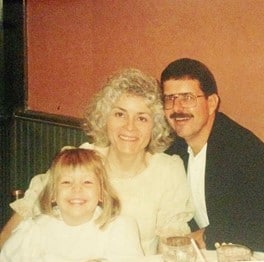

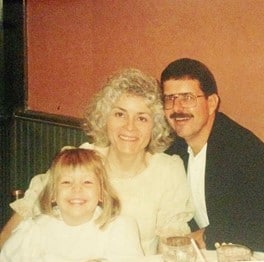

Sarah with her foster, later adoptive, family

The next day we packed up all my belongings, including a bright orange slide for myself and my siblings to play with, and hopped in the car. I was ecstatic. I really liked my foster parents, but I missed my mom and my older sisters. In my mind we could play with our Barbie Dolls together. Maybe they would teach me how to braid my hair the way they did.

I shared my excitement with my foster family who responded to me with joy, never outwardly expressing the pain they were going through. Much later, I learned that what we were experiencing was “reunification”. This is the process in which the state returns children in foster care to their biological home after a temporary time of separation.

Upon my arrival home, I was as idealistic as ever. Sadly, it didn’t take long for my dream house to come tumbling down. I entered a familial war zone. Instead of a room for myself, I went to sleep on a frameless mattress stained with urine. Rather than playing with my sisters, the girls in my family hid in our bathroom from our abusers. The slide given to my family by my foster parents became a target for knife-throwing practice, and my mother was unable to stop it.

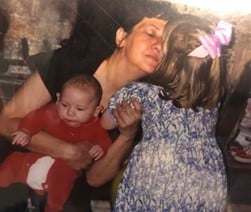

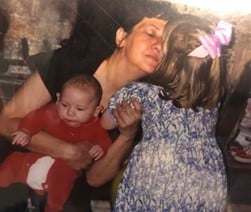

Sarah with her birth mother

I know now my birth mother desperately wanted to save us from the difficulties we faced. She utilized every resource she had to try and fix our broken family. But the problems in our home were too systemic, too evolved, for one person to repair.

She was a woman facing multiple setbacks. Today she would be described as an individual at the epicenter of disadvantage in society because she had multiple sources of oppression. She was oppressed because of her sex, race, and social class as well as her mental disability. My mother was also a victim of domestic violence, married to multiple predators in her lifetime.

I see it more clearly at age thirty-one, but as a child I wrestled with beliefs I’d categorize presently as fiction. It was fictional to believe that my mother’s love for me would be enough to overcome the ramifications of poverty. It was fictional to believe that my home environment would improve when we were eating insects off the floor for food. And it was fictional to believe that those who abused us would stop without intervention and therapy by mental health professionals.

As I suffered in my mother’s house, I slowly began to realize that my childhood dream of being safely together would never happen, and that is exactly why, when I returned to my foster family, I approached them with questions.

“Why didn’t you come get me?” I asked my foster mother. She tried her best to explain to me, only a few years removed from toddlerhood, that she had no choice. Returning me to my birth family was the state’s directive. I didn’t understand the process of reunification but continued through tumultuous years of foster care with continued visits and reunification attempts with my birth family.

Ultimately it took nearly eight years for the state of Louisiana to terminate my mother’s parental rights, and in April of 1999, I was officially adopted. I spent the majority of my time as an adolescent in counseling recovering from my “war zone” experience. I grieved the loss of my mother, and I grieved the loss of my siblings all while also sorting through my Christian faith.

It wasn’t until the summer of 2005, the year Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans, that I came to a major conclusion about my life: foster care saved me from a horrendous future. I evacuated the city with my adoptive family in August and returned in September to find out one of my beloved sisters overdosed on drugs. To me, her tragic and premature death was a picture of what often happens to children that don’t find a safe haven in foster care as I did.

The difficult truth is that the outcomes for children in foster care are often poor . Many age out of the system with PTSD, an increased risk of drug addiction and dependence as my sister experienced. The statistics indicate more unpleasant realities about their inability to later form healthy adult relationships. It shows that they may partake in high risk behaviors such as illicit sex, criminal activity, and experience chronic health problems. Even suffer from psychiatric disorders.

Sarah with her adoptive father at her wedding

I started to examine my life in light of this data–tried to understand why my experience was so exceptional–and concluded that it was because I had an exceptional foster family who deeply loved my birth mother and my siblings and who were committed to my continued care regardless of whether they would get to adopt me one day.

They knew foster care had no guarantees. They certainly knew the perfect house I was building could collapse, but they were ready for me if it did. All while knowing I could have psychological problems because of my trauma history. Nonetheless, they lived out Christ’s call to care for orphans. They saw foster care as part and parcel to their pro-life calling.

Today my adoptive parents are an integral part of my life. They walked with me through numerous dark valleys as I sought healing from the past. I know now that I will forever grieve that pink and purple house. I lost my whole family.

Sarah’s adoptive mom with her young son Jesse.

Miraculously though, and by God’s grace, my story does not end in grief. My story didn’t end in drug addiction, exploitation, or suicide because foster care provided me the support I would need for a lifetime. I know too that my comprehensive pro-life ethic first took root under their tutelage and because of their faithful example to love birthmothers and their children.

The post My Perfect House: A Foster Care Story appeared first on Focus on the Family.

Continue reading...

In my heart, I believed that we would be a family free from the clutches of poverty, abuse, and mental illness. Those problems couldn’t coexist with me in the house I was building. I couldn’t wait to see my family again and asked my foster parents if it was time to go.

They gently brushed my blondish hair and told me we wouldn’t be leaving until the morning. “Sarah, we have to wait for Ms. Gloria to meet us at the house.” Ms. Gloria was my social worker from the Department of Children and Family Services in Louisiana where my family resided.

Sarah with her foster, later adoptive, family

The next day we packed up all my belongings, including a bright orange slide for myself and my siblings to play with, and hopped in the car. I was ecstatic. I really liked my foster parents, but I missed my mom and my older sisters. In my mind we could play with our Barbie Dolls together. Maybe they would teach me how to braid my hair the way they did.

I shared my excitement with my foster family who responded to me with joy, never outwardly expressing the pain they were going through. Much later, I learned that what we were experiencing was “reunification”. This is the process in which the state returns children in foster care to their biological home after a temporary time of separation.

Familial “War Zone”

Upon my arrival home, I was as idealistic as ever. Sadly, it didn’t take long for my dream house to come tumbling down. I entered a familial war zone. Instead of a room for myself, I went to sleep on a frameless mattress stained with urine. Rather than playing with my sisters, the girls in my family hid in our bathroom from our abusers. The slide given to my family by my foster parents became a target for knife-throwing practice, and my mother was unable to stop it.

Sarah with her birth mother

I know now my birth mother desperately wanted to save us from the difficulties we faced. She utilized every resource she had to try and fix our broken family. But the problems in our home were too systemic, too evolved, for one person to repair.

She was a woman facing multiple setbacks. Today she would be described as an individual at the epicenter of disadvantage in society because she had multiple sources of oppression. She was oppressed because of her sex, race, and social class as well as her mental disability. My mother was also a victim of domestic violence, married to multiple predators in her lifetime.

I see it more clearly at age thirty-one, but as a child I wrestled with beliefs I’d categorize presently as fiction. It was fictional to believe that my mother’s love for me would be enough to overcome the ramifications of poverty. It was fictional to believe that my home environment would improve when we were eating insects off the floor for food. And it was fictional to believe that those who abused us would stop without intervention and therapy by mental health professionals.

“Why didn’t you come get me?”

As I suffered in my mother’s house, I slowly began to realize that my childhood dream of being safely together would never happen, and that is exactly why, when I returned to my foster family, I approached them with questions.

“Why didn’t you come get me?” I asked my foster mother. She tried her best to explain to me, only a few years removed from toddlerhood, that she had no choice. Returning me to my birth family was the state’s directive. I didn’t understand the process of reunification but continued through tumultuous years of foster care with continued visits and reunification attempts with my birth family.

Foster Care Saved Me

Ultimately it took nearly eight years for the state of Louisiana to terminate my mother’s parental rights, and in April of 1999, I was officially adopted. I spent the majority of my time as an adolescent in counseling recovering from my “war zone” experience. I grieved the loss of my mother, and I grieved the loss of my siblings all while also sorting through my Christian faith.

It wasn’t until the summer of 2005, the year Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans, that I came to a major conclusion about my life: foster care saved me from a horrendous future. I evacuated the city with my adoptive family in August and returned in September to find out one of my beloved sisters overdosed on drugs. To me, her tragic and premature death was a picture of what often happens to children that don’t find a safe haven in foster care as I did.

The difficult truth is that the outcomes for children in foster care are often poor . Many age out of the system with PTSD, an increased risk of drug addiction and dependence as my sister experienced. The statistics indicate more unpleasant realities about their inability to later form healthy adult relationships. It shows that they may partake in high risk behaviors such as illicit sex, criminal activity, and experience chronic health problems. Even suffer from psychiatric disorders.

Foster Care Essential to Pro-Life Work

Sarah with her adoptive father at her wedding

I started to examine my life in light of this data–tried to understand why my experience was so exceptional–and concluded that it was because I had an exceptional foster family who deeply loved my birth mother and my siblings and who were committed to my continued care regardless of whether they would get to adopt me one day.

They knew foster care had no guarantees. They certainly knew the perfect house I was building could collapse, but they were ready for me if it did. All while knowing I could have psychological problems because of my trauma history. Nonetheless, they lived out Christ’s call to care for orphans. They saw foster care as part and parcel to their pro-life calling.

Today my adoptive parents are an integral part of my life. They walked with me through numerous dark valleys as I sought healing from the past. I know now that I will forever grieve that pink and purple house. I lost my whole family.

Sarah’s adoptive mom with her young son Jesse.

Miraculously though, and by God’s grace, my story does not end in grief. My story didn’t end in drug addiction, exploitation, or suicide because foster care provided me the support I would need for a lifetime. I know too that my comprehensive pro-life ethic first took root under their tutelage and because of their faithful example to love birthmothers and their children.

The post My Perfect House: A Foster Care Story appeared first on Focus on the Family.

Continue reading...