Barbarian

Member

Well, a couple of years ago, but one more predicted transitional found.

Nature 472, 181–185 (14 April 2011) | doi:10.1038/nature09921

Transitional mammalian middle ear from a new Cretaceous Jehol eutriconodont

Jin Meng , Yuanqing Wang & Chuankui Li

Abstract

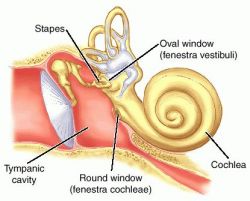

The transference of post-dentary jaw elements to the cranium of mammals as auditory ossicles is one of the central topics in evolutionary biology of vertebrates. Homologies of these bones among jawed vertebrates have long been demonstrated by developmental studies; but fossils illuminating this critical transference are sparse and often ambiguous. Here we report the first unambiguous ectotympanic (angular), malleus (articular and prearticular) and incus (quadrate) of an Early Cretaceous eutriconodont mammal from the Jehol Biota, Liaoning, China. The ectotympanic and malleus have lost their direct contact with the dentary bone but still connect the ossified Meckel|[rsquo]|s cartilage (OMC); we hypothesize that the OMC serves as a stabilizing mechanism bridging the dentary and the detached ossicles during mammalian evolution. This transitional mammalian middle ear narrows the morphological gap between the mandibular middle ear in basal mammaliaforms and the definitive mammalian middle ear (DMME) of extant mammals; it reveals complex changes contributing to the detachment of ear ossicles during mammalian evolution.

Nature 472, 181–185 (14 April 2011) | doi:10.1038/nature09921

Transitional mammalian middle ear from a new Cretaceous Jehol eutriconodont

Jin Meng , Yuanqing Wang & Chuankui Li

Abstract

The transference of post-dentary jaw elements to the cranium of mammals as auditory ossicles is one of the central topics in evolutionary biology of vertebrates. Homologies of these bones among jawed vertebrates have long been demonstrated by developmental studies; but fossils illuminating this critical transference are sparse and often ambiguous. Here we report the first unambiguous ectotympanic (angular), malleus (articular and prearticular) and incus (quadrate) of an Early Cretaceous eutriconodont mammal from the Jehol Biota, Liaoning, China. The ectotympanic and malleus have lost their direct contact with the dentary bone but still connect the ossified Meckel|[rsquo]|s cartilage (OMC); we hypothesize that the OMC serves as a stabilizing mechanism bridging the dentary and the detached ossicles during mammalian evolution. This transitional mammalian middle ear narrows the morphological gap between the mandibular middle ear in basal mammaliaforms and the definitive mammalian middle ear (DMME) of extant mammals; it reveals complex changes contributing to the detachment of ear ossicles during mammalian evolution.