Barbarian

Member

- Jun 5, 2003

- 33,356

- 2,560

Long-sought Fossil Mammal With Transitional Middle Ear Found

Paleontologists from the American Museum of Natural History and the Chinese Academy of Sciences announce the discovery of Liaoconodon hui, a complete fossil mammal from the Mesozoic found in China that includes the long-sought transitional middle ear. The specimen shows the bones associated with hearing in mammals - the malleus, incus, and ectotympanic- decoupled from the lower jaw, as had been predicted, but held in place by an ossified cartilage that rested in a groove on the lower jaw. The new research, published in Nature this week, also suggests that the middle ear evolved at least twice in mammals, for monotremes and for the marsupial-placental group.

"People have been looking for this specimen for over 150 years since noticing a puzzling groove on the lower jaw of some early mammals, " says Jin Meng, curator in the Division of Paleontology at the Museum and first author of the paper. "Now we have cartilage with ear bones attached, the first clear paleontological evidence showing relationships between the lower jaw and middle ear."

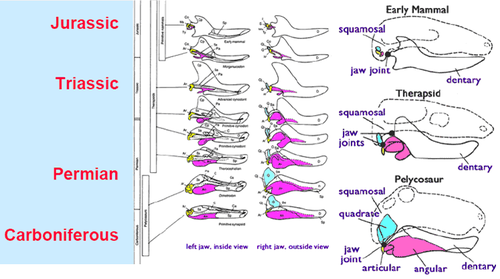

Mammals - the group of animals that includes egg-laying monotremes like the platypus, marsupials like the opossum, and placentals like mice and whales - are loosely united by a suite of characteristics, including the middle ear ossicles. The mammalian middle ear, or the area just inside the ear drum, is ringed in shape and includes three bones, two of which are found in the joint of the lower jaw of living reptiles. This means that during the evolutionary shift from the group that includes lizards, crocodilians, and dinosaurs to mammals, the quadrate and articular plus prearticular bones separated from the posterior lower jaw and became associated with hearing as the incus and malleus.

The transition from reptiles to mammals has long been an open question, although studies of developing embryos have linked reptilian bones of the lower jaw joint to mammalian middle ear bones. Previously discovered fossils have filled in parts of the mammalian middle-ear puzzle. An early mammal, Morganucodon that dates to about 200 million years ago, has bones more akin to a reptilian jaw joint but with a reduction in these bones, which functioned for both hearing and chewing. Other fossils described within the last decade have expanded information about early mammals-finding, for example, that ossified cartilage still connected to the groove was common on the lower jaws of early mammals. But these fossils did not include the bones of the middle ear.

The new fossil described this week, Liaoconodon hui, fills the gap in knowledge between the basal, early mammaliaforms likeMorganucodon, where the middle ear bones are part of the mandible and the definitive middle ear of living and fossil mammals.

http://www.amnh.org/our-research/sc...sil-mammal-with-transitional-middle-ear-found

Paleontologists from the American Museum of Natural History and the Chinese Academy of Sciences announce the discovery of Liaoconodon hui, a complete fossil mammal from the Mesozoic found in China that includes the long-sought transitional middle ear. The specimen shows the bones associated with hearing in mammals - the malleus, incus, and ectotympanic- decoupled from the lower jaw, as had been predicted, but held in place by an ossified cartilage that rested in a groove on the lower jaw. The new research, published in Nature this week, also suggests that the middle ear evolved at least twice in mammals, for monotremes and for the marsupial-placental group.

"People have been looking for this specimen for over 150 years since noticing a puzzling groove on the lower jaw of some early mammals, " says Jin Meng, curator in the Division of Paleontology at the Museum and first author of the paper. "Now we have cartilage with ear bones attached, the first clear paleontological evidence showing relationships between the lower jaw and middle ear."

Mammals - the group of animals that includes egg-laying monotremes like the platypus, marsupials like the opossum, and placentals like mice and whales - are loosely united by a suite of characteristics, including the middle ear ossicles. The mammalian middle ear, or the area just inside the ear drum, is ringed in shape and includes three bones, two of which are found in the joint of the lower jaw of living reptiles. This means that during the evolutionary shift from the group that includes lizards, crocodilians, and dinosaurs to mammals, the quadrate and articular plus prearticular bones separated from the posterior lower jaw and became associated with hearing as the incus and malleus.

The transition from reptiles to mammals has long been an open question, although studies of developing embryos have linked reptilian bones of the lower jaw joint to mammalian middle ear bones. Previously discovered fossils have filled in parts of the mammalian middle-ear puzzle. An early mammal, Morganucodon that dates to about 200 million years ago, has bones more akin to a reptilian jaw joint but with a reduction in these bones, which functioned for both hearing and chewing. Other fossils described within the last decade have expanded information about early mammals-finding, for example, that ossified cartilage still connected to the groove was common on the lower jaws of early mammals. But these fossils did not include the bones of the middle ear.

The new fossil described this week, Liaoconodon hui, fills the gap in knowledge between the basal, early mammaliaforms likeMorganucodon, where the middle ear bones are part of the mandible and the definitive middle ear of living and fossil mammals.

http://www.amnh.org/our-research/sc...sil-mammal-with-transitional-middle-ear-found