Lewis

Member

Seizures: When 'electrical brainstorm' hit

Mon June 18, 2012

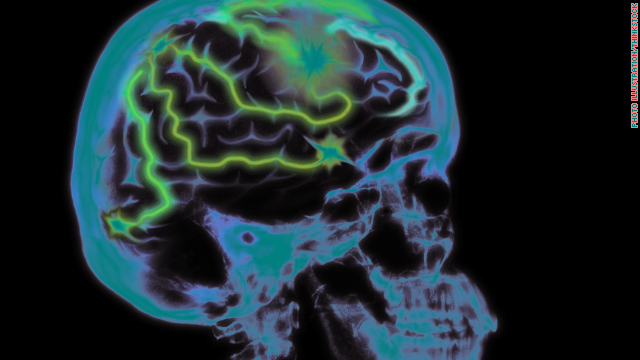

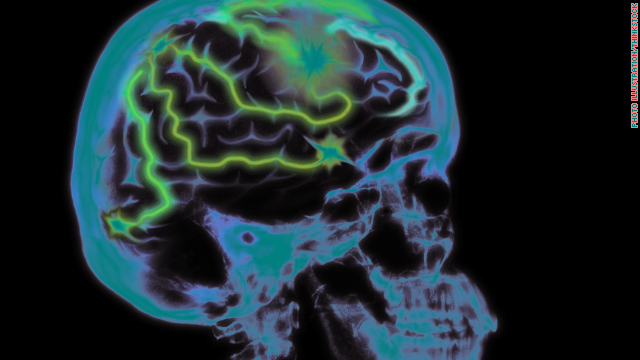

During a seizure, brain cells keep firing instead of discharging electrical energy in a controlled manner.

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

Nathan Jones was 18 when he had his first seizure. He lost consciousness, fell off his porch and woke up to hear a paramedic yelling at him to name the president of the United States.

Over the next four years, Jones had 10 or 11 more generalized tonic-clonic (grand mal) seizures. He had seizures in his dorm room, while driving, in class and on a trip to New York.

Jones, 29, has epilepsy, and feels so strongly about educating people about the complex brain disorder and the seizures that stem from it that he became the project coordinator for the Epilepsy Foundation of Greater Los Angeles.

When he heard that U.S. Commerce Secretary John Bryson had a seizure while driving in Southern California, Jones was empathetic.

"It seems that some people have been so quick to judge him. It just goes to show you that there are so many misconceptions," Jones said of Bryson, who is under investigation after allegedly causing two car accidents last week.

"It's such a dramatic and stressful period as it is. I can only imagine what he is going through. This is all happening in the spotlight. If he would have had a heart attack, the public would have just thrown sympathy his way."

It is unclear what caused Bryson's seizure, which officials said was his first.

Some doctors and those living with seizures said the Bryson incident is an opportunity to dispel myths about seizures and explain just how common they are. Bryson is not the first high-ranking public official to have a seizure: Five years ago, Chief Justice John Roberts had a seizure that caused him to fall while at his summer home. Roberts also had a seizure in 1993.

Nathan Jones has produced a short film about what it's like to have an epileptic seizure.

Up to 10% of the world's population will have at least one seizure, the World Health Organization says, and having one seizure does not signal epilepsy.

Withdrawal of certain medications, antibiotics, alcohol withdrawal and extremely low blood sugar can all cause seizures, experts say. Epilepsy, a neurological condition, is usually diagnosed after someone has had at least two seizures that were not caused by a medical condition, according to the Epilepsy Therapy

Project.

Epilepsy is the fourth most common neurological disorder in the United States after migraine, stroke and Alzheimer's disease, and yet it is widely misunderstood, according to the Institute of Medicine. In fact, one in 26 people in the United States will develop epilepsy at some point in their lifetime.

Seizures occur when the electrical system of the brain malfunctions. The brain cells keep firing instead of discharging electrical energy in a controlled manner. The result can be a surge of energy through the brain, causing unconsciousness and muscle contractions. Some seizures, however, are barely noticed.

"You can have your first seizure at any point," said Dr. Joseph Sirven, who worked on anInstitute of Medicine report called "Epilepsy Across the Spectrum: Promoting Health and Understanding" released in March.

"It's actually very common to present with seizure at an older age. Oftentimes, you will look for potential cerebrovascular implications," such as stroke, hemorrhages or a tumor, said Sirven, who is chairman of the Department of Neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Arizona, chairman of the Epilepsy Foundation's Professional Advisory Board and editor-in-chief of Epilepsy.com.

"If you remember, Ted Kennedy had presented with a seizure and that led to the diagnosis of a brain tumor. It's not that uncommon. But not all seizures are brain tumors."

Dr. Christianne Heck, medical director of the University of Southern California Comprehensive Epilepsy Program in Los Angeles, calls epilepsy a "hidden disorder."

"Epilepsy doesn't have a poster child like muscular dystrophy. We just don't have anybody who is willing to talk about it," said Heck, who also worked on the Institute of Medicine report. "I think it's important for people to understand you can be OK. You can function at a very high level. Most of the time, 70% of the cases are easily controlled, easily managed."

Yet a large number of people go about their daily lives hiding the fact that they have seizures because they are concerned such disclosures would negatively affect their lives, she said.

"Lots of things contribute to that stigma and that embarrassment," Heck said. "It's a disorder of the brain, and the public doesn't understand it in terms of what it looks like and what it is and what they need to do to keep someone from having a seizure safe."

The fact that seizures can happen any time and in public makes it difficult for some people with epilepsy, she added.

Kevin Oliver, 46, of Los Angeles knows that problem all too well.

"I know that's one of the main fears for people that have epilepsy -- telling other people. You always have that fear of that person's reaction. We have a wall up sometimes," he said. "I think it's a fear we don't want to be judged in a certain way. We're trying to protect ourselves."

But the aerospace technician said it's important for anyone with a seizure disorder to be honest about his or her medical condition. Everyone at work knows he has epilepsy, he said.

"They are very protective of me. I do feel it's something you need to express. You shouldn't keep it hidden. You do want people to know."

Still, it isn't always easy, Oliver said.

"You feel embarrassed when you are coming out of it," he said. "There are so many people standing around looking at you. They are looking at you out of concern, but that's not your first reaction."

When Oliver heard about Bryson, he said he was immediately relieved no one was hurt.

"I have had one before when I was driving," Oliver said. "I know the fear behind that. When you come out of it, you don't know what happened. You are just hoping you didn't injure anyone."

Frank Chavez, 63, a retired parole agent in California, had his first seizure in 1999 while driving his daughter's car. He was later told that he got off the freeway, hit a black van and just kept going.

"I lived about two blocks away and instinctively I just drove that car right home," he said. "I started walking up the driveway."

He was putting the key in the door when he heard a man screaming. The man was yelling that Chavez should have stopped after the accident.

Chavez has frequent and serious seizures, is on medication and has even undergone surgeries to try to stop them.

"This is a disease that jumps out of nowhere," said Chavez's wife, Patricia. "We used to call it the monster. We never knew when it would jump out."

When her husband's seizures begin, Patricia Chavez first asks God to let him live. Then she looks at the clock to time the seizure and tries to turn her husband on his side to help him breathe. She tries to stay calm and talk to her husband.

At some point, Frank Chavez understands his wife is talking to him. "I'll hear my wife and she'll tell me, 'Frank, Frank,' " he said. "I do hear her. I just can't do the things she wants me to do."

The lack of control is something you have to deal with, said people living with seizures.

"You become 200% vulnerable to your surroundings and to (other people's) knowledge of what is happening to you," said Jones of the Epilepsy Foundation of Greater Los Angeles.

"If I have a seizure in public and I'm next to a bunch of broken glass, are they going to be able to react? Are they going to forgive me when I can't react and listen to them? It's part of the education process. Your brain has just suffered this huge electrical brainstorm."

Heck said anyone living with epilepsy that is not well-controlled should seek out neurologists who are highly trained in managing epilepsy. She and others urge people to seek out information about seizures and epilepsy.

"The biggest misconception is that it is a disease of the young and that it is something you are only going to see in a younger kid or a younger adult," Sirven said. "This is actually a condition that affects all age groups, and older adults seem to have a higher propensity for this. This is not uncommon."

Soo Ihm, 41, was diagnosed with epilepsy when she was 6 or 7. She said she gets frustrated that more people with epilepsy don't speak out. People who haven't had seizures need to understand there is nothing to be afraid of, she said.

"People don't understand the full spectrum of seizures and also the idea of a seizure," Ihm said. "It looks so different and people don't know what to do when you are having one. Epilepsy has such a range of experiences. Seizures can last from a second to several minutes. You can be fully aware, you can lose total consciousness or anywhere in between. "

CNN

Mon June 18, 2012

During a seizure, brain cells keep firing instead of discharging electrical energy in a controlled manner.

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- Up to 10% of the population will have at least one seizure, World Health Organization says

- Having one seizure does not signal epilepsy, and there can be many causes, experts say

- Seizures occur when the electrical system of the brain malfunctions

- Many people go about their daily lives hiding the fact that they have seizures, doctor says

Nathan Jones was 18 when he had his first seizure. He lost consciousness, fell off his porch and woke up to hear a paramedic yelling at him to name the president of the United States.

Over the next four years, Jones had 10 or 11 more generalized tonic-clonic (grand mal) seizures. He had seizures in his dorm room, while driving, in class and on a trip to New York.

Jones, 29, has epilepsy, and feels so strongly about educating people about the complex brain disorder and the seizures that stem from it that he became the project coordinator for the Epilepsy Foundation of Greater Los Angeles.

When he heard that U.S. Commerce Secretary John Bryson had a seizure while driving in Southern California, Jones was empathetic.

"It seems that some people have been so quick to judge him. It just goes to show you that there are so many misconceptions," Jones said of Bryson, who is under investigation after allegedly causing two car accidents last week.

"It's such a dramatic and stressful period as it is. I can only imagine what he is going through. This is all happening in the spotlight. If he would have had a heart attack, the public would have just thrown sympathy his way."

It is unclear what caused Bryson's seizure, which officials said was his first.

Some doctors and those living with seizures said the Bryson incident is an opportunity to dispel myths about seizures and explain just how common they are. Bryson is not the first high-ranking public official to have a seizure: Five years ago, Chief Justice John Roberts had a seizure that caused him to fall while at his summer home. Roberts also had a seizure in 1993.

Nathan Jones has produced a short film about what it's like to have an epileptic seizure.

Up to 10% of the world's population will have at least one seizure, the World Health Organization says, and having one seizure does not signal epilepsy.

Withdrawal of certain medications, antibiotics, alcohol withdrawal and extremely low blood sugar can all cause seizures, experts say. Epilepsy, a neurological condition, is usually diagnosed after someone has had at least two seizures that were not caused by a medical condition, according to the Epilepsy Therapy

Project.

Epilepsy is the fourth most common neurological disorder in the United States after migraine, stroke and Alzheimer's disease, and yet it is widely misunderstood, according to the Institute of Medicine. In fact, one in 26 people in the United States will develop epilepsy at some point in their lifetime.

Seizures occur when the electrical system of the brain malfunctions. The brain cells keep firing instead of discharging electrical energy in a controlled manner. The result can be a surge of energy through the brain, causing unconsciousness and muscle contractions. Some seizures, however, are barely noticed.

"You can have your first seizure at any point," said Dr. Joseph Sirven, who worked on anInstitute of Medicine report called "Epilepsy Across the Spectrum: Promoting Health and Understanding" released in March.

"It's actually very common to present with seizure at an older age. Oftentimes, you will look for potential cerebrovascular implications," such as stroke, hemorrhages or a tumor, said Sirven, who is chairman of the Department of Neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Arizona, chairman of the Epilepsy Foundation's Professional Advisory Board and editor-in-chief of Epilepsy.com.

"If you remember, Ted Kennedy had presented with a seizure and that led to the diagnosis of a brain tumor. It's not that uncommon. But not all seizures are brain tumors."

Dr. Christianne Heck, medical director of the University of Southern California Comprehensive Epilepsy Program in Los Angeles, calls epilepsy a "hidden disorder."

"Epilepsy doesn't have a poster child like muscular dystrophy. We just don't have anybody who is willing to talk about it," said Heck, who also worked on the Institute of Medicine report. "I think it's important for people to understand you can be OK. You can function at a very high level. Most of the time, 70% of the cases are easily controlled, easily managed."

Yet a large number of people go about their daily lives hiding the fact that they have seizures because they are concerned such disclosures would negatively affect their lives, she said.

"Lots of things contribute to that stigma and that embarrassment," Heck said. "It's a disorder of the brain, and the public doesn't understand it in terms of what it looks like and what it is and what they need to do to keep someone from having a seizure safe."

The fact that seizures can happen any time and in public makes it difficult for some people with epilepsy, she added.

Kevin Oliver, 46, of Los Angeles knows that problem all too well.

"I know that's one of the main fears for people that have epilepsy -- telling other people. You always have that fear of that person's reaction. We have a wall up sometimes," he said. "I think it's a fear we don't want to be judged in a certain way. We're trying to protect ourselves."

But the aerospace technician said it's important for anyone with a seizure disorder to be honest about his or her medical condition. Everyone at work knows he has epilepsy, he said.

"They are very protective of me. I do feel it's something you need to express. You shouldn't keep it hidden. You do want people to know."

Still, it isn't always easy, Oliver said.

"You feel embarrassed when you are coming out of it," he said. "There are so many people standing around looking at you. They are looking at you out of concern, but that's not your first reaction."

When Oliver heard about Bryson, he said he was immediately relieved no one was hurt.

"I have had one before when I was driving," Oliver said. "I know the fear behind that. When you come out of it, you don't know what happened. You are just hoping you didn't injure anyone."

Frank Chavez, 63, a retired parole agent in California, had his first seizure in 1999 while driving his daughter's car. He was later told that he got off the freeway, hit a black van and just kept going.

"I lived about two blocks away and instinctively I just drove that car right home," he said. "I started walking up the driveway."

He was putting the key in the door when he heard a man screaming. The man was yelling that Chavez should have stopped after the accident.

Chavez has frequent and serious seizures, is on medication and has even undergone surgeries to try to stop them.

"This is a disease that jumps out of nowhere," said Chavez's wife, Patricia. "We used to call it the monster. We never knew when it would jump out."

When her husband's seizures begin, Patricia Chavez first asks God to let him live. Then she looks at the clock to time the seizure and tries to turn her husband on his side to help him breathe. She tries to stay calm and talk to her husband.

At some point, Frank Chavez understands his wife is talking to him. "I'll hear my wife and she'll tell me, 'Frank, Frank,' " he said. "I do hear her. I just can't do the things she wants me to do."

The lack of control is something you have to deal with, said people living with seizures.

"You become 200% vulnerable to your surroundings and to (other people's) knowledge of what is happening to you," said Jones of the Epilepsy Foundation of Greater Los Angeles.

"If I have a seizure in public and I'm next to a bunch of broken glass, are they going to be able to react? Are they going to forgive me when I can't react and listen to them? It's part of the education process. Your brain has just suffered this huge electrical brainstorm."

Heck said anyone living with epilepsy that is not well-controlled should seek out neurologists who are highly trained in managing epilepsy. She and others urge people to seek out information about seizures and epilepsy.

"The biggest misconception is that it is a disease of the young and that it is something you are only going to see in a younger kid or a younger adult," Sirven said. "This is actually a condition that affects all age groups, and older adults seem to have a higher propensity for this. This is not uncommon."

Soo Ihm, 41, was diagnosed with epilepsy when she was 6 or 7. She said she gets frustrated that more people with epilepsy don't speak out. People who haven't had seizures need to understand there is nothing to be afraid of, she said.

"People don't understand the full spectrum of seizures and also the idea of a seizure," Ihm said. "It looks so different and people don't know what to do when you are having one. Epilepsy has such a range of experiences. Seizures can last from a second to several minutes. You can be fully aware, you can lose total consciousness or anywhere in between. "

CNN