How do you know? Compression of tissue tends to make it add cells. I see claims, but no data. So I'm skeptical.

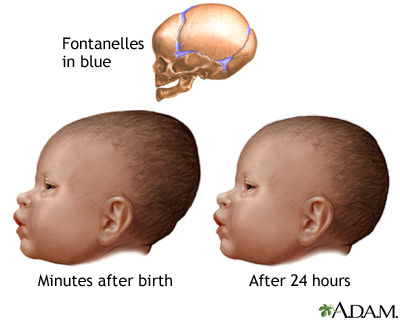

They don't. The same sutures exist. Many of the skulls exhibit what anatomists call sagittal synostosis, a condition where the two parietal bones prematurely fuse from pressure. It's commonly found in other examples of skull binding. And all the other bones that are not intentionally distorted are, from all the pictures available, entirely human. It would be astonishing if an alien race happened to have exactly the same bones in the skull as humans.

So your argument is that binding can change the frontal and parietal bones, but not the occipital? Ask yourself why the foramen magnum is so far forward in humans, relative to apes, and then think about the way binding changes the distribution of weight in the skull. You'll have your answer.

How could that happen?

Here, this is assuming what what was proposed to prove.

Me too. The discovery of a third subspecies of recent H. sapiens was an amazing thing. Turns out Denesovans, like Neandertals, have left their genes with our own subspecies. Tibetan genes for high altitude adaptation seem to have been Denesovan. And unlike the long skull stories, this one actually happened.

Knowing what one is talking about is a big advantage, yes. For example, your guy is stunned by two holes at the top of some of these skulls. He assumes that they aren't human. Anatomists call them "parietal emissary foramina", and they are a normal variation in human skulls.

No.

http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/craniosynostosis/symptoms-causes/dxc-20256926

Premature fusing of bones can obliterate sutures, and pressure is one way it can happen. However, these skulls clearly show two parietal bones, in areas where they were not bound.

Just as we all have a tibia and fibula in our legs, ulna and radius in our arms, four chambers to our heart and the same number of vertebra in our spine.

No. For example, there are many people who happen to lack the last few vertebrae. Coccygeal agenesis usually has no symptoms at all, since the coccyx is vestigial; people with this condition normally never know it, unless an X-ray happens to illustrate the fact. Some people even do fine without a portion of their sacrum.

No, not always.

Nope. As you see, it's merely premature fusion of sutures. And it's not remarkable, given the binding that would cause it to happen.

Well, it was more for endurance and athleticism than mere strength. But as you know, modern evolutionary theory shows that such attempts are impractical, due to the many generations of selective breeding required.

Both have been sequenced. Identical, right down to the individual atoms and structural orientation.

We're talking identical, not similar. Outside of the primates, I don't think we have any large molecules that are identical. But it's possible. I would expect that if it is, it would be in a highly conserved function like cytochrome C or neurotransmitters.

(Edit) Often, a molecule will be somewhat different in different species, but still works fine between species. This is because much of the molecule is merely "spacers" to make it the right size and shape. So long as the active site is identical, it will still work between species.

Think of a key to a lock. The part that goes into the lock has to be identical, but it doesn't matter at all what the end you hold is like.

So you're leaning to the idea that this particular gorilla gene, if inserted into a human genome, would not make the recipient "not human?"

It wouldn't work with any purines or pyrimidines we know about. Unzipping would be impossible, so the molecule wouldn't function at all.