Sacred Name Bible

Bible translations that use Hebraic forms of God's personal name (YHWH) / From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Sacred Name Bibles are

Bible translations that consistently use

Hebraic forms of the

God of Israel's personal name, instead of its English language translation, in both the

Old and

New Testaments. Some

Bible versions, such as the

Jerusalem Bible, employ the name

Yahweh, a

transliteration of the Hebrew

tetragrammaton (YHWH), in the English text of the Old Testament, where traditional English versions have LORD.

Most Sacred Name versions use the name

Yahshua, a

Semitic form of the

name Jesus.

With the exception The Lockman Foundation, which owns the Legacy Standard Bible, none of the Sacred Name Bibles are published by mainstream publishers. Instead, most are published by the same group that produced the translation. Some are available for download on the Web. Very few of these Bibles have been noted or reviewed by scholars outside the

Sacred Name Movement.

Some Sacred Name Bibles, such as the

Hallelujah Scriptures, are also considered

Messianic Bibles due to their significant Hebrew style. Therefore they are commonly used by

Messianic Jews as well.

Historical background

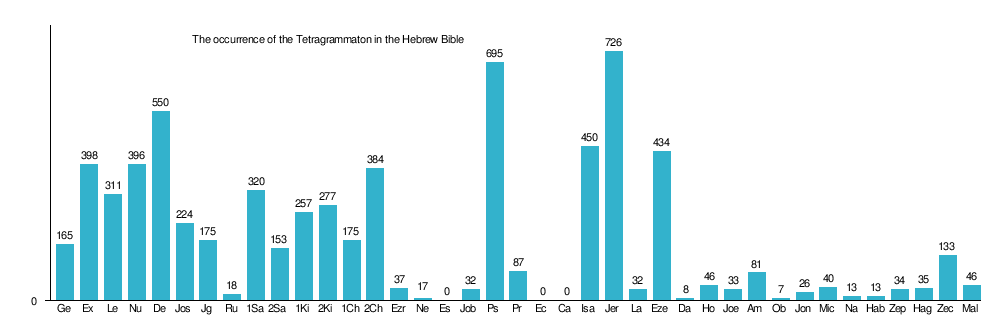

YHWH occurs in the

Hebrew Bible, and also within the Greek text in a few manuscripts of the

Greek translation found at

Qumran among the

Dead Sea Scrolls. It does not occur in early manuscripts of the Greek New Testament. Although the Greek forms

Iao and

Iave do occur in magical inscriptions in the

Hellenistic Jewish texts of

Philo,

Josephus and the

New Testament use the word

Kyrios ("Lord") when citing verses where YHWH occurs in the Hebrew.

For centuries, Bible translators around the world did not transliterate or copy the

tetragrammaton in their translations. For example, English Bible translators (Christian and Jewish) used LORD to represent it. Modern authorities on Bible translation have called for translating it with a vernacular word or phrase that would be locally meaningful. The

Catholic Church has called for maintaining in the

liturgy the tradition of using "the Lord" to represent the tetragrammaton, but does not forbid its use outside the liturgy, as is shown by the existence of Catholic Bibles such as the

Jerusalem Bible (1966) and the

New Jerusalem Bible (1985), where it appears as "Yahweh", and place names that incorporate the tetragrammaton are not affected.

A few Bible translators, with varying theological motivations, have taken a different approach to translating the tetragrammaton. In the 1800s–1900s at least three English translations contained a variation of YHWH. Two of these translations comprised only a portion of the New Testament. They did not restore YHWH throughout the body of the New Testament.

In the twentieth century, Rotherham's

Emphasized Bible was the first to employ full transliteration of the tetragrammaton where it appears in the Bible (i.e., in the Old Testament).

Angelo Traina's translation,

The New Testament of our Messiah and Saviour Yahshua in 1950 also used it throughout to translate Κύριος, and

The Holy Name Bible containing the Holy Name Version of the Old and New Testaments in 1963 was the first to systematically use a Hebrew form for sacred names throughout the Old and New Testament, becoming the first complete Sacred Name Bible.

Aramaic primacy

Main article:

Aramaic primacy

Some translators of Sacred Name Bibles hold to the view that the

New Testament, or significant portions of it, were originally written in a Semitic language,

Hebrew or

Aramaic, from which the Greek text is a translation.[

citation needed] This view is colloquially known as "Aramaic primacy", and is also taken by some academics, such as Matthew Black. Therefore, translators of Sacred Name Bibles consider it appropriate to use Semitic names in their translations of the New Testament, which they regard as intended for use by all people, not just Jews.

Although no early manuscripts of the New Testament contain these names, some

rabbinical translations of Matthew did use the tetragrammaton in part of the Hebrew New Testament.

Sidney Jellicoe in

The Septuagint and Modern Study (Oxford, 1968) states that the name YHWH appeared in Greek Old Testament texts written for Jews by Jews, often in the

Paleo-Hebrew alphabet to indicate that it was not to be pronounced, or in Aramaic, or using the four Greek letters

PIPI (

Π Ι Π Ι) that physically imitate the appearance of Hebrew יהוה,

YHWH), and that

Kyrios was a Christian introduction. Bible scholars and translators such as

Eusebius and

Jerome (translator of the

Latin Vulgate) consulted the

Hexapla, but did not attempt to preserve sacred names in Semitic forms.

Justin Martyr (second century) argued that YHWH is not a personal name, writing of the "namelessness of God".

George Lamsa, the translator of

The Holy Bible from Ancient Eastern Manuscripts: Containing the Old and New Testaments (1957), believed the New Testament was originally written in a Semitic language, not clearly differentiating between

Syriac and Aramaic. However, despite his adherence to a Semitic original of the New Testament, Lamsa translated using the English word "Lord" instead of a Hebraic form of the divine name.

Accuracy or popularity

Sacred Name Bibles are not used frequently within Christianity, or Judaism. Only a few translations replace

Jesus with Semitic forms such as

Yeshua or

Yahshua. Most English Bible translations translate the tetragrammaton with

LORD where it occurs in the Old Testament rather than use a

transliteration into English. This pattern is followed in languages around the world, as translators have translated sacred names without preserving the Hebraic forms, often preferring local names for the creator or highest deity, conceptualizing accuracy as semantic rather than phonetic.

The limited number and popularity of Sacred Name Bible translations suggests that phonetic accuracy is not considered to be of major importance by Bible translators or the public. The translator

Joseph Bryant Rotherham lamented not making his work into a Sacred Name Bible by using the more accurate name Yahweh in his translation (pp. 20 – 26), though he also said, "I trust that in a popular version like the present my choice will be understood even by those who may be slow to pardon it." (p. xxi).